Who’s responsible for strong communities?

And how do organizational missions drive engagement choices? (Reading Time: About 5 minutes)

In the early days of my landscape architecture practice, I worked on lots of community garden projects. Seattle,the Emerald City, calls them P-Patches, and they are some most powerful spaces for place-based community building.

Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods (DON) stewards the P-Patch Community Garden program. DON is a somewhat unusual government agency. It was established in the 1990’s with a goal of empowering people through neighborhood planning and organizing. Visionary at the time, it has sadly been neutered by successive mayoral administrations antipathetic to bottom-up power.

Some P-Patches reside on land owned by Seattle Parks and Recreation (SPR). And back when I was working on all those community garden projects, there was some interdepartmental tension over the presence and management of P-Patches on SPR property.

The details aren’t important, but a wise city-savvy friend explained to me that the root cause of this conflict came down to a difference in mission: DON’s mission focused on building community, whereas SPR’s mission focused on maximizing recreational opportunities.

This story has stuck with me ever since. How does the mission of an organization drive its downstream decision making? And is this why we don’t see more community building within community engagement processes?

I use “community building” here as shorthand for the work of connecting, bridging, and supporting place-based communities. In our era of social fragmentation, this work is urgent, and community engagement is dripping with restorative potential. But, as discussed last time, most common engagement processes don’t tap into their community building potential.

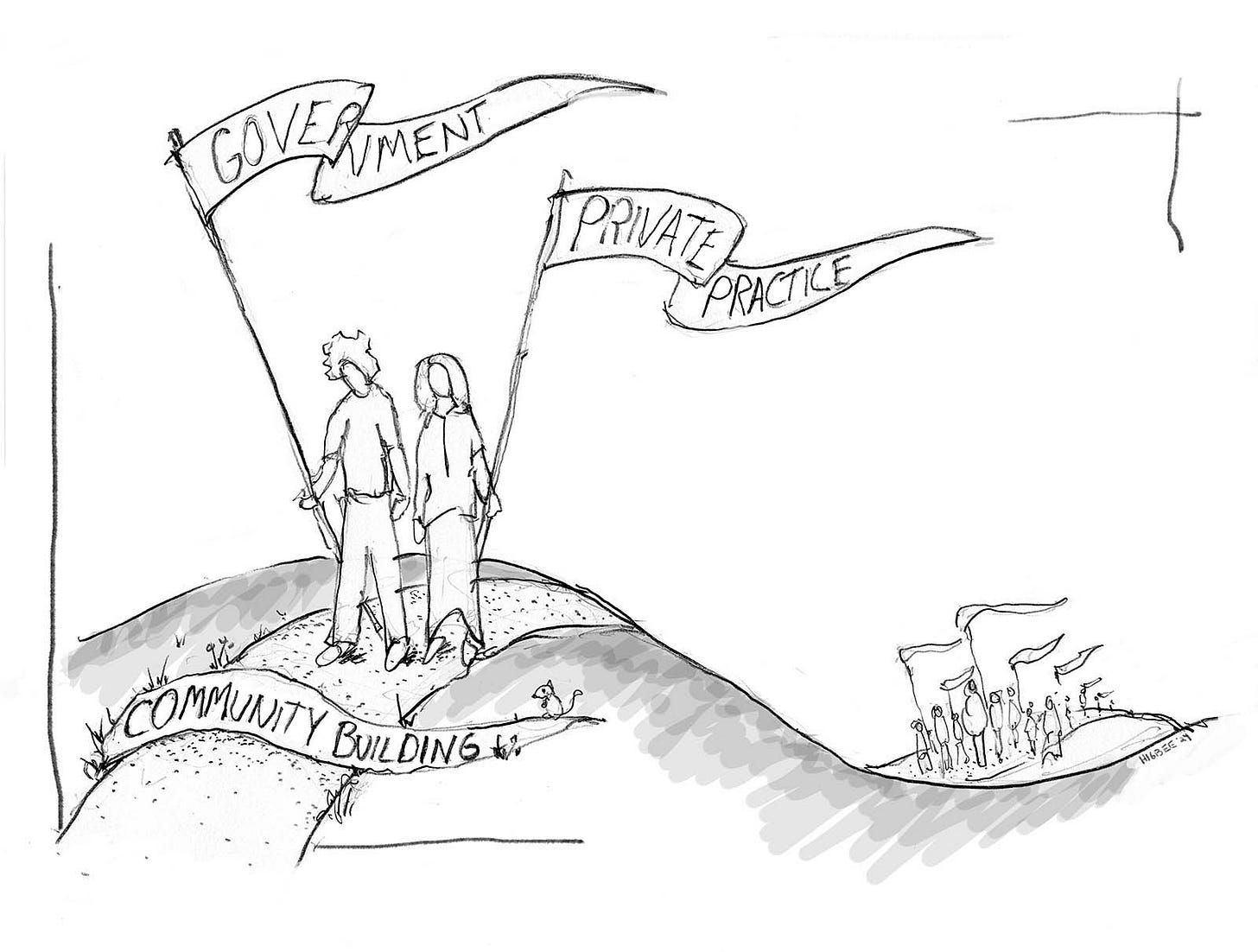

How many government agencies have community building as part of the mission, like the DON? Or how about planning and design consulting firms?

If community building isn’t part of their mission, can we really expect them to dedicate the requisite resources for this work within their community engagement practice?

If community building isn’t part of their mission, can we really expect them to dedicate the requisite resources for this work within their community engagement practice?

And if community building *is* in an organization’s mission, then why don’t we see more of it?

Survey Insights

I decided to plumb these questions in my recent survey on the Practice of Community Engagement. If you need a refresher on the survey and its scope, check out this earlier post with an overview.

In the survey, I asked survey participants to rank their response to the statement: “Community building is an explicit part of the mission or purpose of our firm/agency/organization.” They could choose from 1 (Strongly Disagree) through 5 (Strongly Agree). Here are the results:

What do you see?

First, it’s not surprising that those representing non-profit and community groups responded more positively to this question.

Second, it’s notable that most government and private practices also responded affirmatively, with a combined average of about 3.7.

Maybe I’m overly cynical, but my experience suggests that most community engagement processes do not center community building work. Instead, they focus on soliciting input to inform design or planning decisions. This perspective was recently bolstered by a 2024 survey of parks agencies from the Trust for Public Land, where respondents said they were nearly five times more likely to ‘inform’ the public than to ‘empower’ them.

So the survey results suggest a strong discrepancy between mission and practice. What gives?

Missions, of course, are very aspirational. Even while flying a flag of community building, support for this deeper (and hard to quantify) work typically dries up when the rubber meets the project-budget road. Why? Stay tuned - we’ll explore this more in our next post.

Also, like the word “natural” on food packaging, the terms “community” and “building community” are vague enough that just about anyone can claim that mantle.

Lastly, community building can happen through non-engagement means. For example, a parks department may extol the community-building benefits of the park space they just built, but still employ engagement strategies during the planning process that eschew social connections. Separating the process from the product is a critical distinction, and perhaps not articulated clear enough in this survey question.

The bigger picture

All of this begs a bigger question: whose’ responsibility is it to support strong communities? We are facing overlapping social crises of loneliness and cultural polarization, underpinned by a collapse of the associations and rituals that support placed-based community-life. Who will help us out of this mess?

All of this begs a bigger question: whose’ responsibility is it to support strong communities? Who will help us out of this mess?

Is it local governments? Unfortunately, most governments are structured to focus on providing services and responding to deficits within their communities. They don’t see themselves in the business of building community. This is partly because our conception of local government, forged the early days of our Democratic laboratory, assumes the pre-existence of strong place-based communities. That government might have a responsibility to support socially cohesive community life, rather than just govern, is a novel conception. That’s why Seattle’s DON was so precedent-setting.

How about private consultants, like design and planning firms? I know many people with within these fields that are passionate about community building work.

However, most are beholden to the constraints of a market-based system. Capitalism simply doesn’t place value on the invisible connections between people that comprise community. As a result, consultants prioritize providing excellence and delivering solutions to their clients, whatever those agendas may be.

Models like the UK’s Participatory City provide a glimmer of hope for new approaches to social infrastructure supported through philanthropy. If you need a primer, check out my previous post, “The Best Community Building Model You’ve Never Heard Of.” This is why I’ve been working to bring the Participatory City model to the U.S., through Every One Every Day Yesler Terrace.

Outside of that, it’s left to scrappy, passionate, and heroic community-based organizations working directly in their communities to make the world a better place. Such groups are often underfunded, volunteer-based, and chasing scraps of extra cash floating around the spaces of the richest country on earth. Sigh.

I’ve been encouraged by some concerted efforts to support such groups through government and philanthropic efforts. For example, I appreciate the Learning Center at Weave: The Social Fabric Project at the Aspen Institute, a project of New York Times columnist David Brooks. Or I recently enjoyed learning about San Francisco’s In Real Life Accelerator, with their mantra “Building In-Person Communities is Ridiculously Hard,” through our friends at the Connective Tissue Substack. Other examples abound.

But given the state of our society, this is an all hands-on-deck-moment that should prompt every sector to take a hard look at the their mission.

~Eric

LOOKING FOR STORIES TO SHARE

Do you have a great example of how a community engagement process helped a community restitch is fraying social fabric, or go from “Us vs Them” to “We.” I’d love to talk to you. Please reach out.