Survey Insights: How much Community Building are We Doing?

Results from our National Survey reveal challenges with the state of our dialogue and practice. (Reading time: just under 4 minutes)

Survey Insights: How much Community Building are We Doing?

Results from our National Survey reveal challenges with the state of our dialogue and practice. (Reading time: just under 4 minutes)

Community engagement has incredible potential. In our time of deepening social fragmentation, it can bridge differences and build common identity amongst diverse residents. It can foster a sense of belonging and cultivate the lasting connections that comprise a strong social fabric.

But here’s the catch: most engagement processes don’t tap this potential. Contemporary community engagement focuses on soliciting input to inform design or planning, but not on fostering relationships between different types of people. Open-houses and on-line surveys are good examples.

The shorthand I use for this is “community building” vs. “community engagement”. They are not the same thing.

So then, why not? In a time of increasing social polarization, isolation, and fragmentation, what barriers keep practitioners from adopting more community building outcomes? What practices are most common? Where are the opportunities for systemic change?

I’ve been seeking to uncover answers to these questions and establish a baseline of understanding about our community engagement practices. In October 2023, I launched the Practice of Community Engagement Survey, and solicited responses through the end of March 2024. I'm now starting to process what I've heard.

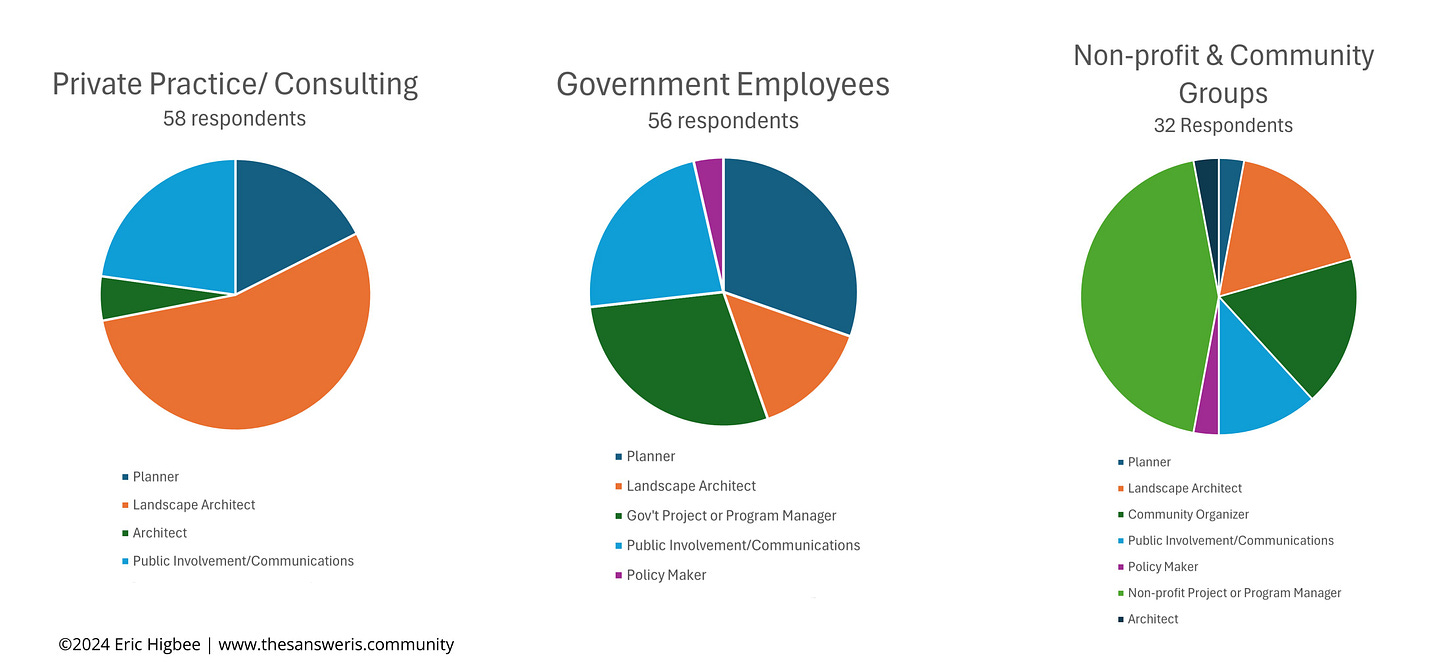

I garnered about 150 responses from a wide array of folks involved with community engagement. Admittedly, it’s not quite as many respondents as I hoped. I was surprised at how challenging it was to get people to take a three-minute survey, even with the promise of a potential prize. BTW: Congrats to the three winners! I hope they enjoy their new books from Island Press Books.

Below is a snapshot at the make-up of the respondents. I’ve broken them up into three major categories: private practice/consultants, government officials, and non-profits/community members. Although in the real world these lines can be fuzzy, I believe these categories are helpful here as they represent the key relationships to community processes.

Respondents were from all over the country, although a third were from Washington State where I practice and teach. Consultant firms were of a wide variety of sizes. Governments were largely represented by local agencies, with a smattering at the regional, state, and federal scales. Non-profit and community groups tended to be organizations that were actively working to cultivate community in their local communities.

I want to understand how much community building practitioners are doing within their current community engagement work. So, for one of my first questions, I asked: “Approximately what percentage of your community engagement work involves place-based community building as an intentional part of its process?”

In retrospect, this question could’ve been better constructed for several reasons. And I think these reasons are symptomatic of the poor state of discourse and vocabulary within community engagement practice.

1. There wasn’t space within the survey to ensure respondents understood the difference between community building and community engagement.

I have found that these terms are often conflated in common parlance and practice. Practitioners often claim community building outcomes even when there was nothing but just regular ‘ol community engagement.

2. The questions does not do enough to distinguish between process (ex. outreach, meetings, etc.) and product (ex. a park or building design that supports community interactions).

The perspectives of practitioners, especially those in the built environment, are typically biased towards their work’s products. They assume that if their product contributed to community building, then by extension any associated community engagement also counts as community building.

While there’s some truth to this, we need to have a clearer separation between process and product so they we can evaluate each for their social impact.

3. The question doesn’t do enough to distinguish between aspiration and actual practice.

Many folks feel like they are doing community building in their engagement work. But a closer look often reveals that when the rubber meets the road, project outcomes do not explicitly prioritize community building aspirations. This is often because community building work is not supported with enough resources or time.

Illusions of community building are also buoyed when project consultants or managers get warm fuzzies in their interactions with community members during the course of their work. Fostering relationship between community members and project representatives is not a substitution for fostering lasting relationships between community members.

Now that we have those caveats out of the way, the chart below shows the responses I received in the survey. For the reasons stated above, I believe these results over-represent the amount of community building currently occurring in practice. You should interpret them with caution. At best, they show a self-reported maximum.

Government and private practices are reporting only about 40-50% of their work involves community building. Naturally, the non-profit and community groups report over 70%.

What do you think about these results?

I'll admit that I may be overly cynical in my interpretation of the questions and results.

But as we’ll see next time, a closer look at the most common engagement practices (as reported in the survey) shows a distinct lean towards tools and techniques that don’t do much community building.

Stay tuned for more Practice of Community Engagement Survey insights!

PS. Were you forwarded this email? Sign-up to receive your very own missives delivered directly to your mailbox.