Beyond Design: How to Create Public Spaces for Social Cohesion

To leverage the built environment for social cohesion, look beyond design to what happens AFTER a space is built. (Reading Time: about 3 and a half minutes)

Hi everyone!

I decided to migrate The Answer is Community from Mailchimp to Substack.

Substack, for those who aren’t familiar with it, is an online platform for writers. It offers some distinct advantages for authors like myself, including the option for readers to become paid subscribers (anyone? anyone?). It also has great app that makes it easy to keep-up on other your favorite writers, like Jonathan Haidt, Heather Cox Richardson, and more.

For the Answer is Community, there’s nothing you need to do. I’ve migrated your email addresses over to Substack, and you should continue to receive posts into your email inbox on a regular basis. Subscription is still free.

I suspect that for some of you, Substack may pierce the spam filters that were previously misdirecting my Mailchimp emails. If you are someone who is just now seeing my posts: welcome aboard! The good news is that all of my previous posts are on my Substack page, and you can catch up on what you missed here.

I’m also concerned that I may loose a few folks in the transition, so I will be sending one last email with Mailchimp to round-up any stragglers. I apologize for the redundancy. If you’ve received this email, you are all good.

To give this Substack thing a test-run, I’m republishing a favorite post from 2023, with a few updates. Check it out below. Enjoy!

~Eric

Beyond Design: How to Create Public Spaces for Social Cohesion

To leverage the built environment for social cohesion, look beyond design to what happens AFTER a space is built. (Reading Time: about 3 and a half minutes)

Those of us who shape the built environment often take pride in our work creating the public living rooms and front porches of civil society.

We follow the guiding light of Jane Jacob’s and her seminal 1961 book, Death and Life of Great American Cities, which extols the virtues of vibrant public spaces as an essential component of healthy and diverse neighborhoods.

Parks, plazas, streets, courtyards – all that wonderful social mixing must help foster tolerance and inclusion amongst different groups of people, right? Don’t our public spaces somehow counteract the socially fragmenting forces pushing our society into epidemics of loneliness and polarization?

Not so fast.

I’ve got bad news for you.

First, the social routines underpinning Jane Jacob’s insights simply don’t exist anymore for most people.

Over the past few decades, massive changes to our daily routines have decimated the incidental interactions that cultivate “middle-ring” relationships. These are the relationships with people in our neighborhoods with whom we are friendly, but not intimate. Historically they have been the heart of what we refer to as "community." Their decline is well-documented by Marc Dunkelman in The Vanishing Neighbor, and elsewhere.

And without those routines and relationships, there’s little evidence that public spaces alone result in greater tolerance or interactions of people of different groups.

There is little evidence that public spaces alone result in greater tolerance or interactions of people of different groups.

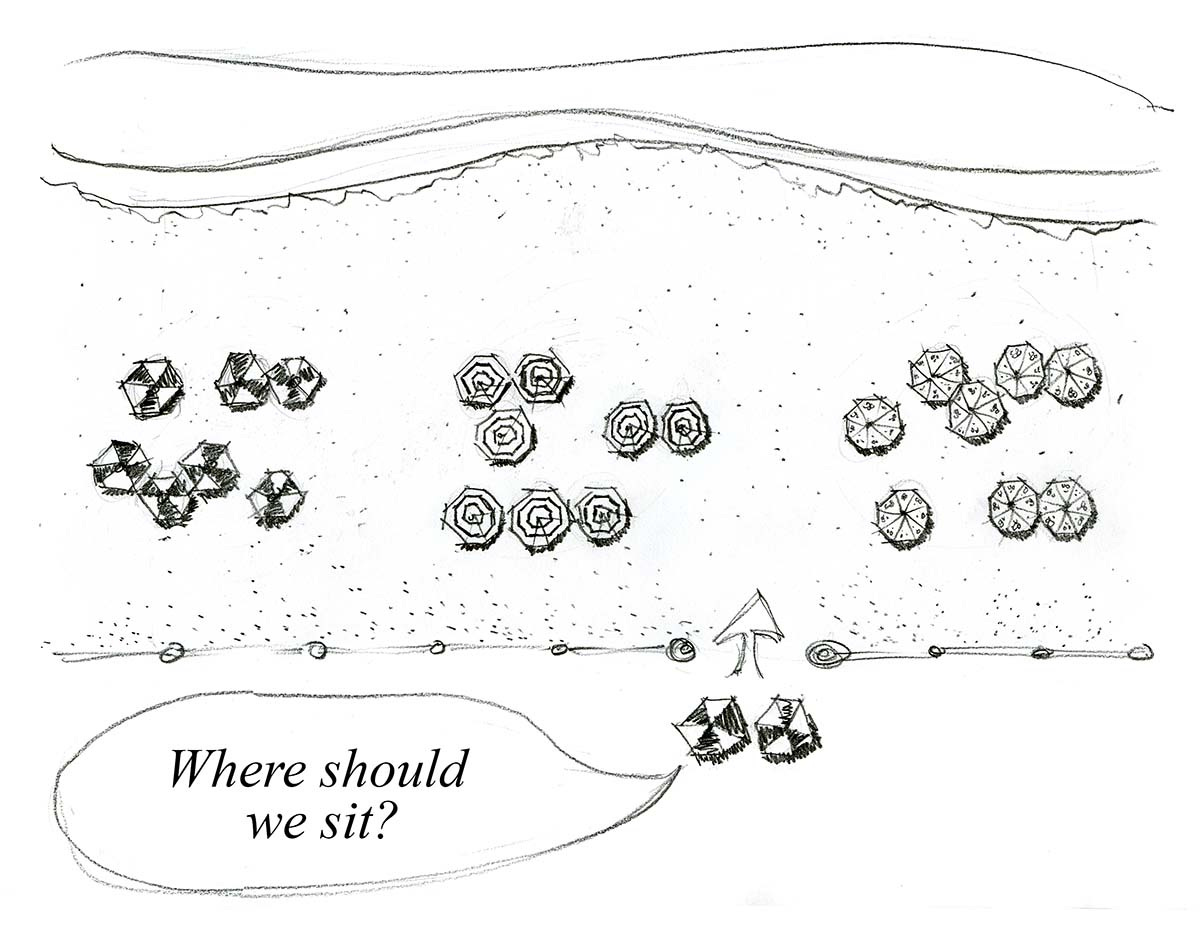

The reasons why are complicated, but it's basically a public-space version of why all the black kids are sitting together in the cafeteria. It's driven by the sociological concept of homophily, or the self-segregating tendency that draws people into contact with those with whom they are similar.

You’ve probably seen this in action at a local public space, say a swimming beach. There’s the area where all the LGTBQ+ folks gather…there’s the area for parents and kids…over there are the Latinx families…and on and on. There’s actually a fair amount of research across the world showing that this kind of self-segregation is common.

Even the best award-winning designs can’t overcome how our homophilic hard-wiring manifests in our public spaces.

And it doesn’t help that our smartphone addictions keep us tethered to our screens, even in public spaces. Really, have you looked around recently? It’s zombie-land out there. It used to be impossible to go through life without constantly talking to strangers, but now those moments are few and far between.

Because of our self-segregating impulses and technological addictions, cultivating intergroup interaction and connection requires an intervening force or structure: a cultural norm, a social institution, governing oversight, or just something you sign-up for that facilitates interactions with others.

Therefore, in shaping of the built-environment, the biggest opportunities to bridge different groups of people are the bookends of a typical design and construction process: the upfront community engagement, or the subsequent programming and operations.

The biggest opportunities to bridge different groups of people and nurture those “middle-ring” relationships bookend the design and construction process

Regular readers will know that this blog’s focus has been on leveraging that upfront community engagement process - the meeting, sharing, visioning, and building together in place-based communities - for such community-building outcomes.

But what about after spaces are built?

So it was with great interest that I recently picked up a copy of “Socioeconomic Mixing” from the group Reimagining Civic Commons (RCC). It’s one of the few publications I’ve seen that addresses this issue.

Besides emphasizing a foundation of good public space design (yes - this is still important!), RCC outlines some compelling approaches to programming public spaces to counteract self-segregation and foster the kind of intergroup contact that bridges social-economic and racial/ethnic boundaries.

Here’s a summary of their top recommendations:

Host Programming that Goes Beyond Events:

Events are great, but smaller repeating events provide more opportunities for deeper connections among different groups of people. A regularly occurring outdoor class, a market, or exercise group, for example. We can achieve greater impact by overlapping smaller multiple events, and by letting public spaces serve as a platform for co-creation of events by community members.

Staff to Intentionally Welcome

Staffing a space with welcoming public space ambassadors can go a long way to making people feel included and facilitating encounters between people of different groups. Hiring should reflect the diversity of the community and can be layered onto existing maintenance roles.

Adopt the Outcome and Measure

Public space managers should make socio-economic mixing an explicit outcome of their work, and regularly evaluate their outcomes so that they can adapt and adjust accordingly. RCC provides a compelling framework, Measuring the Civic Commons, and an interesting DIY toolkit, Measuring What Matters, to help with this work. You may also want to look at Gehl’s Institute’s Public Life Diversity Toolkit.

This last point is an especially important one that I will take up in the coming months: How do we measure something invisible, like the strength of the social connections between different groups? Stay tuned for a deep dive.

The phenomena of homophily in public spaces begs bigger questions about our civil society. If we are wired for self-segregation, what cultural or governing institutions are working to keep our society inclusive and tolerant? Whose responsibility is it to steward those? And in face of such massive fragmentation in our civil society, how do we make radical investments that foster social cohesion, belonging, and inclusion?

And what about the challenges of our macro-scale self-segregating choices about where we live, ala Bill Bishop’s The Big Sort?

While we ponder these questions, thanks to RCC we have a road map for how to start with programming public spaces. Let’s begin there.